Dear friends,

Whilst on a recent trek to the majestic Sawtooth mountains, one of my sons captured the above photo during a morning of fishing. What an image—the kind that sets narratives running. A plethora of tales could be spun around this single word picture.

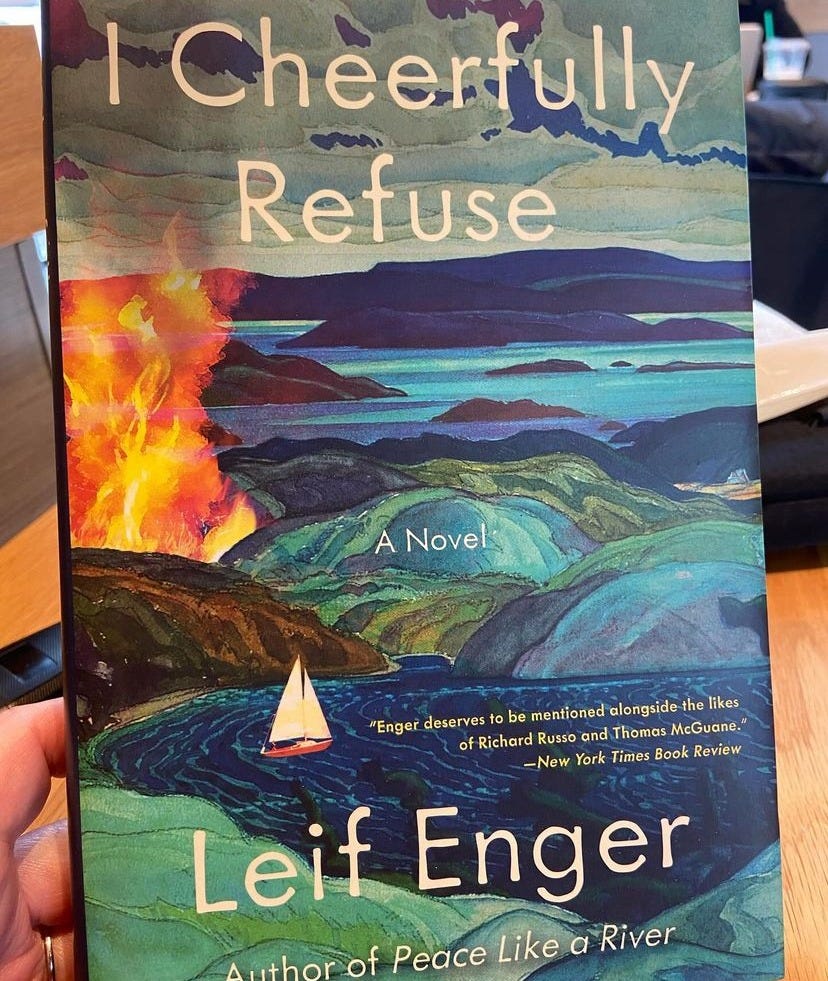

Having just finished I Cheerfully Refuse by Leif Enger, a somewhat dark and foreboding story, I’ve been pondering the sadder themes of life: themes such as grief, loss, and brokenness. Themes that render life askew, and the image seemed a perfect encapsulation for my thoughts.

Enger’s newest title is about a consumed-with-grief man named Rainy who takes to The Great Lakes in a sailboat after the murder of his wife, Lark. As part quest-seeker, part fugitive from the murderers, the narrative follows Rainy’s voyage—one which helps to unfold both his sorrow and the mysterious crime.

The quest portion of the tale has Rainy seeking his wife’s ghost among the Slate Islands, a location integral to the genesis of their love story. Brokenhearted and driven by the delusional hope of finding Lark, he forges through tumultuous waters, literal and metaphorical, to reach his destination.

While there is much I could say about this book (it’s a worthy read), what I want to talk about today is Rainy’s grief. Or more aptly, grief in general.

Reading I Cheerfully Refuse, especially the first half of the book, brought stark reminders of another title I read this past winter, The Year of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion. The memoir, released in 2005, was a National Book Award winner and follows Didion’s grieving process after losing her husband to a “massive coronary event” that took place in the course of an evening meal at home. The opening lines to the book read:

Life changes fast.

Life changes in an instant.

You sit down to dinner and life as you know it ends.

The question of self-pity.

Didion’s memoir is achingly honest and—as the title foreshadows—focuses on her mental struggle to accept her husband’s passing. Catapulted from her normal existence, she finds herself grasping for a life that has slipped away in a blink. Like Rainy in I Cheerfully Refuse, it leaves her irrational at times. The third chapter opens:

“The power of grief to derange the mind has in fact been exhaustively noted.”

It’s also been noted that death is the great equalizer; no man escapes the trauma induced by it—nor the thing itself. I assert the threat of death, and a multitude of other heartrending circumstances, can be just as equalizing, but death is so very final on this side of heaven.

No matter how glossy or glowing one’s life, when death and darkness slink under the door of even the finest dwelling, they shock its inhabitants to the core. And grief, especially the kind that barrels in unexpectedly, has the power to completely derail us. The truth is, at least for a time, it should. Death and brokenness in their many forms are, after all, a curse.

When my oldest son (the same one who took the photo) was seven, he was diagnosed with a nine-vertebrae long spinal cord tumor. The night after the MRI exposed the slinking darkness that had slipped into our lives, I sat on the stairs opposite our front door. I was waiting for my husband to return from work. We had, of course, corresponded throughout the day after receiving the news, but he needed to finish his evening shift at the hospital.

So, despite a foreboding and horrific blow, I had to come home, put dinner on the table, get the kids bathed, and tuck them into bed on my own. Normal life proceeded as if normal life had not just been stolen from us.

With the house finally still, I sank onto the stairs and tried to reckon with our new reality. My son was in grave danger. The possibility of death loomed over us. I was broken by it, and I was terrified.

I think sometimes we delude ourselves about the “normalness” of death. Its sureness makes it seem the natural rhythm of things. There are myriad scientific or even poetic words referring to death: it is inevitable after all, and we may as well name it. Accept it. Even embrace it. But when it actually arrives, it feels anything but normal and rhythmic. Quite the opposite. It is jarring, traumatizing, and most unequivocally wrong.

In the days following my son’s diagnosis, I made phone calls to extended family, sent out emails to friends, and wrote Facebook posts. People needed to know, and we needed prayer. One early response that made its way to my inbox struck me mightily. So much so, that it has stayed with me through all these years.

This friend offered no hollow apologies. There were no platitudes cloaked in Christianese. Instead, she simply said, “There are some things that just shouldn’t be.”

I can’t tell you what solace that statement brought and how often I’ve applied its truth to other circumstances—and offered the same words to others. A life-threatening tumor was not normal; things were not as they should be. If the world were as God originally intended it, tumors wouldn’t exist. And one certainly didn’t belong in my son’s spinal cord.

But alas, we are fallen beings living in a fallen land. Things, in fact, are not as God intended, as any student of the Bible knows.

Reading Leif Enger’s book and revisiting The Year of Magical Thinking caused me to pick up another memoir that has been sitting on my shelf for some time.

The Last Sweet Mile, by Allen Levi is a beautiful tribute to the author’s brother, Gary, who died of cancer in 2012.

The narrative of Gary’s final year of life is used by Allen Levi as a springboard to share various memories and anecdotes and to expound on Gary’s personhood. Levi writes tenderly about his brother’s life, and it’s a deserving and lovely recollection.

But it’s also a testament to the wrongness of death.

Allen Levi is a disciple of Christ as was his brother. His words give evidence to their deep belief in the gospel. In his final year, Gary—especially as sickness took hold—longed to be with Jesus. What’s more, Levi had every confidence that Gary would, indeed, go to be with the Lord. Yet when his brother departed, that knowledge did not exonerate him or his family from the depth of sorrow and loss, from “how much our world had been diminished in his absence.”

I loved this book for its honest sorrow. One particular chapter titled “Sadness” was especially meaningful in regard to grief. Levi relays a conversation he had among his Thursday men’s Bible study—a group that at the time of writing had been meeting for some eighteen years.

After Gary grew sick, one of the men posed a question: “Do you think we get sadder as we get older? If we are maturing and gaining wisdom as we should, do we at the same time become sadder somehow? Is it okay, maybe even right, to be sad?”

The men had been reading through Ecclesiastes and had been pondering “with much wisdom comes much sorrow; the more knowledge, the more grief.” The consensus came that “life lived honestly is a saddening journey…How could any healthy, loving soul see the ruination, the suffering, the self-induced hardships of humanity and not be disheartened by them?”

Grief over brokenness is a proper response.

I think of Jesus at the grave of Lazarus, weeping. He knew that in mere moments he would raise his friend from death. Yet he still wept. Doesn’t that strike you as profound? Did he weep because of the grief on display? Or the despair caused by loss of life? Or was he weeping because death was the antithesis of his heart for mankind—because things weren’t as they should be?

And yet…

Allen Levi asserts that his brother would say that “sadness, that gnawing sense of incompleteness, that yearning, might well be the grace of God drawing our hearts Christward.” Christ followers know there is hope. Grief isn’t the end:

“When the perishable puts on the imperishable, and the mortality puts on the immortality, then shall come to pass the saying that is written:

‘Death is swallowed up in victory.

O death, where is your victory?

O death, where is your sting?’”

1 Corinthians 15:54-55 (emphasis mine)

Death and brokenness do not have the final say for those in Christ. Things will be made right. Then is coming.

Still, friends, on this side of things, death stings.

Even as believers, it is sometimes right to weep and grieve. There is a time for every matter under heaven. We should offer hope to a world gone awry, but for ourselves and friends in a period of difficulty, loss, or mourning, we should also give space for a little delusion and derange.

We must let grief have its proper place.

I hope you will find your way to the lovely titles today, and I especially hope that your current season is one of joy instead of grief. But if things are not as they should be, please reach out. Truly.

I would love to lend a heart and ear to your sorrow.

Tiffany

Then is coming! Amen.

Love this (and you) so much. ❤️

Poignant and thought provoking. Thank you for your words. I'm a stage III oral cancer survivor and now autoimmune disease warrior. Grief comes in all types of packages.